A wide variety of medical conditions can lead to itchy skin. One of those conditions, atopic dermatitis (eczema), affects 10 million children in the US alone. Yet itch is a challenge for researchers and clinicians to quantify, with patient self-report of this subjective experience the only measure to which they can turn. This complicates diagnosis and treatment.

Now, a multidisciplinary group of researchers led by Shuai (Steve) Xu and John Rogers, Northwestern University, Evanston, US, have developed a flexible, bandage-like sensor, powered by a machine learning algorithm, that can objectively measure scratching. The group validated the algorithm in healthy subjects and also showed that the sensor performed well in a clinical population of kids with moderate to severe atopic dermatitis.

Martin Schmelz, who studies itch and pain at the University of Heidelberg, Germany, said the development of the sensor is “simply great.”

“This is an enormously powerful tool that has potential not only to be used in research studies of itch but also in the clinic. If you need to have a specific measure of the amount or intensity of itch, especially overnight, this is very, very helpful,” according to Schmelz, who was not involved with the new research.

The study was published April 30, 2021, in Science Advances.

What seems simple is actually quite complex

Xu, a dermatologist and engineer, said that itch, like pain, can significantly reduce quality of life for patients, but efforts to understand and manage it have been hindered by a lack of measurement tools.

“This is one of the most common nociceptive sensations, but we don’t really have a way to objectively quantify it,” Xu said. “We wanted to create a sensor that could give us a measure so we could understand how bad the itch is and help patients find ways to manage it better.”

So Xu and colleagues developed a sensor that could quantify scratching, the reflexive response to itch sensation. Keum San Chun, University of Texas at Austin, US, co-first author of the study along with Youn Kang and Jong Yoon Lee, both of Northwestern, said one of the biggest challenges at the start was to design something small that could track what are often very small movements, and do so at a high sensing rate.

“We needed a small system that could sample the data faster than commercial devices like an Apple Watch,” said Chun. “With a higher sensing rate, we also would have the opportunity to capture high frequency information associated with scratching activity.”

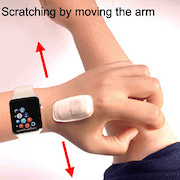

So the team came up with the ADvanced Acousto-Mechanic (ADAM) sensor. This is a soft and flexible sensor, akin to a Band-Aid, that can be attached to the top of the hand, in the curved part of the hand where the thumb meets the forefinger. The sensor not only captures scratching motion but also the small sounds made when a person scratches.

“Scratching is actually a pretty complicated behavior,” said Xu. “Some people scratch with just their fingers. Some use their wrist. Some will just rub or find a way to use their elbow. There are a lot of different ways to do it, and people scratch with a lot of different intensities. This sensor can capture the motion involved with scratching, and it also captures these acoustic-mechanical waves, which are the sounds made when you scratch yourself.”

Capturing scratching and only scratching

The researchers then created a machine learning algorithm to teach the sensor how to differentiate scratching behaviors, regardless of the body location of the scratching, from other common hand motions. The team developed a training dataset for the algorithm by having 10 healthy individuals wear the sensor and perform a variety of activities, including different types of scratching both under and over their clothes, as well as waving their hands, sending text messages, tossing and turning on a bed, typing on a keyboard, or tapping their fingers on a desk. Those activities, performed twice for 35 seconds each, were recorded for the algorithm and classified as either scratching or non-scratching activities to help the algorithm learn the difference.

“We provided scratching data from all locations of the body so the sensor became very good at picking up scratching in any location you might decide to scratch,” said Xu. “We also taught the algorithm not to pick up other movements, like texting or typing, so we could be sure it was only identifying actual scratching behaviors.”

Indeed, the results showed that the algorithm had approximately 90% sensitivity, specificity, and accuracy in the 10 subjects.

Other experiments showed that the ADAM device was better than a wrist-mounted Apple Watch running a mobile app called Itch Tracker. For instance, unlike ADAM, Itch Tracker misclassified hand waving as scratching and couldn't detect scratching on the head. Nor could Itch Tracker detect scratching using only fingers.

Next, to validate the sensor in a clinical population, the group recruited 11 patients with mild to severe eczema, with an average age of 10.5 years. These subjects wore the sensor, as well as a smartwatch, at home on their dominant hand while they slept. The study participants were simultaneously recorded with an infrared video camera, for a total of 46 nights across all participants. To test the accuracy of ADAM, two independent medical student raters watched the videos and annotated when patients scratched, and then the researchers compared that to what the algorithm identified as scratching behaviors. When the investigators did that comparison, they again found that the sensor performed well, with an overall accuracy rate of 99%, 84% sensitivity, and 99% specificity. This was better than results from previous studies of automated scratch detection validated with video data.

“Using infrared cameras to try and measure scratching is quite laborious – you have to go through hours and hours of footage to look at scratching behaviors – so it’s just not feasible for clinicians to do regularly,” said Schmelz. “This sensor could be very helpful to those who want to understand just how much a patient might be scratching at night.”

![The clinical validation was conducted in a natural home environment with predominately pediatric AD [atopic dermatitis] patients (median age, 10.5 years). An IR camera was used to record scratching behavior of human subjects and was manually graded by two clinical research staff members. Photo credit: Jan-Kai Chang, Wearifi Inc. Caption from Chun et al., Sci Adv. 2021 Apr; 7(18).](https://www.iasp-pain.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/02/ItchSensorInline-2.jpg)

Next steps

Xu said the group plans to do further studies in which they will add a second sensor, to the non-dominant hand. They also aim to evaluate ADAM in other conditions, beyond eczema, that cause itch. Overall, the investigators are excited about the potential of the sensor to improve treatment.

“This kind of sensor could be very useful in terms of tracking response to treatment for different conditions that have itch as a symptom,” Xu said. “Especially kids with eczema will often scratch at night. They might not even realize how much they are scratching. This sensor can tell us whether a treatment is working and reinforce adherence. As a doctor, I can look at the sensor output and say, ‘Okay, your kiddo is scratching 30% less and sleeping a lot better with this topical ointment. Let’s keep using it.’ Or we might see that the current treatment isn’t doing as well as we hoped and make the decision to switch to something else.”

Xu added that, in the future, he and the team would like to expand the algorithm to pick up scratching changes that may indicate a disease flare-up. The itch intensity of eczema, for example, can wax and wane, but doctors don’t always understand why. Seeing an uptick of scratching at night could help physicians prescribe preventive treatments before the disease becomes a lot worse and the rash gets too severe or infected.

“Itch can be as debilitating as chronic pain, and it can have really devastating effects on millions of American children,” said Xu. “This sensor could potentially help doctors and patients better manage different diseases [characterized by itch], as well as test potential new treatments for different conditions as the treatments come on the market. There’s a lot we could do with a sensor like this. And, given how many people experience severe itching, it’s important that we do so.”

Kayt Sukel is a freelance writer based outside Houston, Texas.