How do we predict pediatric pain trajectories? Who recovers from pain and for whom does pain persist? These questions were the focus of Laura Simons’ closing keynote address, “Predicting Recovery or Persistence in Pediatric Pain: Innovative Tools and Novel Strategies,” for the Conquering the Hurt Conference on November 3, 2020. This virtual event was organized and hosted through a partnership between the Pain Centre at the Hospital for Sick Children in Toronto, Canada, and Pain in Child Health (PICH), a research training consortium.

While researchers have been making progress toward understanding the factors that may predict whether a child experiences a resolution of their pain or will go on to suffer from persistent pain, there is still a long way to go for a better grasp of these factors. What healthcare providers see in a clinical setting and what investigators know from a research perspective “is just a fraction of the multitude of factors going on in the context of chronic pain,” said Simons, of Stanford University School of Medicine, Stanford, US.

Simons’ work has pinpointed various psychosocial and behavioral factors that are risk factors for the development of chronic pain after surgery in kids, as well as risk factors for the persistence of pain following intensive pain rehabilitation. However, one of the take-home messages from her talk was that to truly understand outcomes for pediatric patients with pain, and to identify a tailored level of care for these patients, larger and more diverse datasets that include information on aspects such as brain structure and function, the immune system, sensory profiles, psychological states, pain intensity, and disability level are needed, as are complex analytical methods to gather and make sense of the data. This is exactly what Simons is now doing with a clinical trial called SPRINT (Signature for Pain Recovery IN Teens), funded by the NIH Heal Initiative.

Predicting pain persistence after surgery

To begin understanding the factors that contribute to the development or persistence of pain, Simons and other researchers have followed children who underwent surgery. After various types of surgical procedures, including spinal fusion, hip preservation, major musculoskeletal surgery, orthopedic procedures, and general surgery, rates of high-level persistent pain ranged from 6% to 38% with follow-ups from one to five years postsurgery (Sieberg et al., 2013Sieberg et al., 2017Rabbitts et al., 2020Rosenbloom et al., 2019). This is an alarmingly large number of children who experience chronic postsurgical pain.

The above studies have also looked at self-reported psychosocial factors that may place a child at risk for developing new chronic pain or maintaining their previous chronic pain following surgery. Worse functional disability levels, more severe pain intensity, poor sleep quality, and greater depressive symptoms emerge as important risk factors.

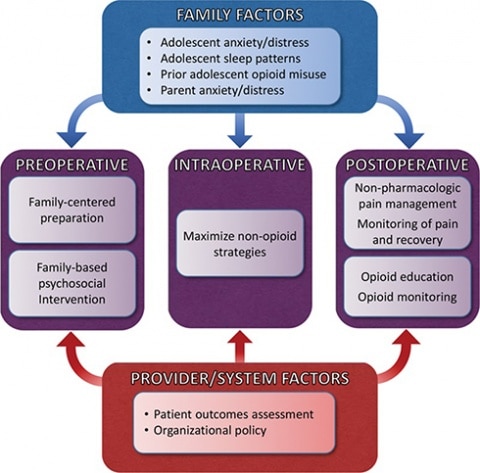

Beyond those aspects, a model has been developed to show family and provider/system factors that may impact the preoperative, intraoperative, and postoperative time frames, and could lead to poor postsurgical outcomes (see figure above). This model provides an important framework for a better understanding of risk factors, how to intervene, and how to improve outcomes. For example, purposeful inclusion of the family in decision making and surgical preparation, as well as education and employing non-pharmacologic strategies for pain management, are proposed to improve postsurgical outcomes for teens and families.

In a nod to her fellow Conquer the Hurt presenters and PICH members, Simons pointed to additional research aiming to improve postsurgical outcomes in teens. For example, Jennifer Stinson of the Hospital for Sick Children and University of Toronto, Canada, and her team have developed a mobile health (mhealth) intervention, iCanCope PostOp, which is now being explored to enhance coping before and after surgery in order to improve postoperative pain management (Birnie et al., 2019). This app is now in development and seeks to include key functions such as tracking pain, providing biopsychosocial pain education, and teaching self-management strategies. Researchers hope these types of projects can help prevent the transition from acute to chronic postsurgical pain in adolescents.

Understanding chronic pain and what level of services are needed

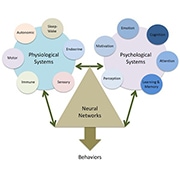

The large focus of Simons’ talk was the multitude of factors that contribute to chronic pain. There is a large, complex network of systems to explore when thinking about chronic pain and pain behaviors, and Simons highlighted aspects of this model (see figure below), which include physiological systems and psychological systems that contribute to changes in the neural networks associated with pain behaviors. In addition to these factors, researchers and clinicians must keep the individual’s developmental level in mind when working with children and teens, as growth and development result in changes to all of the body’s systems.

One way to begin screening patients to determine the level of help they need is through the use of the Pediatric Pain Screening Tool (PPST), developed by Simons. This measure has been validated in youth with mixed chronic pain types as well as pediatric headache. It successfully predicted who would need greater services based on functional disability level and psychosocial risk factors (Simons et al., 2015Simons et al., 2013).

Simons, in partnership with Anna Wilson and Amy Holley, developed another helpful screening tool, called Parent Risk and Impact Screening Measure (PRISM), to assess parents’ psychosocial functioning and how they respond to their child’s pain. PRISM considers the reports that parents give of their own stress, health, psychosocial functioning, and disruption in activities resulting from their child's pain and related disability (Simons et al., 2019). Unlike adults, children present to the clinic with their parents, so it is important to identify which parents need greater support. “We don’t know who needs our support unless we screen for it,” Simons said.

Changes in the brain in response to treatment

Pain researchers, including those in the field of pediatric pain, have increasingly looked to brain imaging to explore changes in the brain that might accompany chronic pain, as well as how pain treatments may reverse those alterations – topics that Simons also addressed during her talk.

For instance, a 2016 fMRI study found that, compared to healthy controls, youth with complex regional pain syndrome (CRPS) exhibited reduced gray matter in sensory, motor, emotional, cognitive, and pain modulatory regions, including the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex, thalamus, and hippocampus (Erpelding et al., 2016). Intensive interdisciplinary psychophysical pain treatment resulted in increased gray matter in those regions.

This study also revealed that the patients with chronic pain showed decreased functional connectivity between descending pain modulatory regions such as the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex and the periaqueductal gray, and that treatment increased functional connectivity between these two brain areas. All in all, brain imaging results suggest a benefit from cognitive tools and physical rehabilitation that modulate functional connectivity between these regions (see Wiech et al., 2008).

Understanding who responds to treatment

While researchers and clinicians are making progress toward improving the lives of many children and adolescents with pain, “our work is not done until we’re able to help everyone,” said Simons. She said that understanding who is most likely to see improvement in their pain following various levels of treatment (e.g., outpatient vs. intensive inpatient) is needed in order to best tailor a treatment approach.

Within the intensive pain rehabilitation program at Boston Children’s Hospital where she used to work, Simons and colleagues have found that approximately 12% of children continue to show significant functional impairment, and 27% continue to report severe pain (7/10 or higher), following intensive treatment. Examination of a number of psychosocial factors has shown that a patient’s readiness to change (e.g., their motivation and readiness to take an active self-management approach to pain) was the most important predictor of improvement in pain and functioning through the course of the intensive pain rehabilitation treatment (Logan et al., 2012Simons et al., 2018).

To dive further into possible differences between treatment responders (those who demonstrate improvement in pain and functioning) and treatment non-responders (those who show no such changes), Simons and colleagues have examined baseline brain imaging profiles of patients who participated in the intensive pain rehabilitation program at Boston Children’s. In this work, which has been submitted for publication, the researchers found differences in the nucleus accumbens and its functional connectivity to the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex, with treatment non-responders having less functional connectivity between these two areas compared to treatment responders. These brain regions and their connectivity are important for motivation and reward as well as top-down pain control. Finally, this study also showed that gray matter density and functional connectivity were similar between healthy controls and treatment responders, but were significantly less in those patients whose pain did not improve. [Editor's note: this research has now been published; see here].

Looking ahead

Researchers are gaining information on brain structure and psychological differences between pediatric patients with chronic pain that resolves, compared to those whose pain persists following treatment. However, the field really needs to bring together a large number of biopsychosocial factors at once to improve the ability to predict outcomes and identify the targeted treatment each patient needs.

Simons is addressing these issues in the SPRINT trial. In partnership with the University of Toronto, Sick Kids, and Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center, her team is enrolling 375 adolescents with musculoskeletal pain who complete multidisciplinary pain treatment to address moderate to severe functional impairment due to pain.

This trial, funded through the National Institutes of Health’s Helping to End Addiction Long-Term (HEAL) Initiative, is obtaining and analyzing a wide range of important biological variables including brain structure and function, immune function, and sensory profiles; psychological states; and clinical endpoint data, including pain intensity and disability. Machine learning approaches will then be used to extract reliable and prognostic bio-signatures to identify recovery trajectories following multidisciplinary pain treatment.

Simons concluded her presentation by highlighting technological advances and the ways in which technology can benefit patients. On a day-to-day level, tools such as daily tracking systems that allow direct feedback to clinicians about symptoms (e.g., pain, mood, anxiety, sleep) can be used to improve pharmacological decision making. Simons said that clinicians should employ a single case design to rigorously test treatment effects and make informed decisions regarding new treatment recommendations (Vlaeyen et al., 2020). Finally, she ended with a call to action for everyone in the field of pediatric pain.

“I challenge us all to incorporate more technology and scientific principles into our clinical work so that we can be scientists with each of our patients, on each day, in order to provide each patient with the best care possible.”

Mary Lynch, PhD, is a postdoctoral fellow at Indiana University School of Medicine, Indianapolis, US, and a PRF Correspondent.