The supportive touch of a romantic partner can have enormous benefits in coping with stressful, threatening, and especially painful situations. To date, the evidence in favor of a role for supportive touch in easing pain has been largely anecdotal. But now, a new brain imaging study provides a detailed investigation of the neurophysiology underlying the phenomenon of touch-induced analgesia, enhancing the understanding of the influence of social factors on pain.

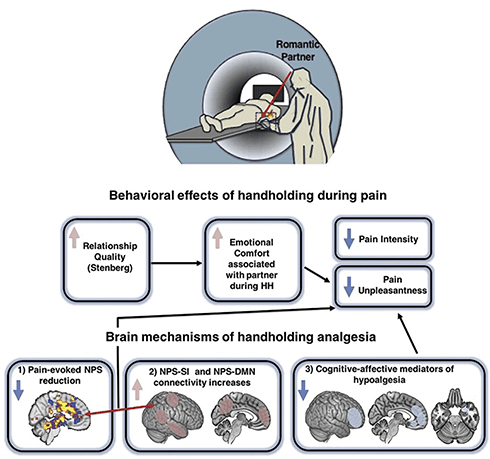

Research led by first author Marina López-Solà, Cincinnati Children’s Hospital, US, and Tor Wager, Dartmouth College, Hanover, US, shows that female volunteers subjected to experimental heat pain reported lower pain intensity and unpleasantness when holding the hand of their male romantic partner. Reductions in pain intensity correlated with self-reported increases in emotional comfort and a higher perceived level of closeness with the romantic partner. Furthermore, evidence from functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) demonstrated that handholding decreased activity in key brain regions known to process pain as well as stress and defensive behaviors.

“This is a study that clearly needed to be done,” said Siri Leknes, University of Oslo, Norway, who studies how the brain encodes hedonic processes such as pleasure and pain but was not involved in the current work. “Most people will have experienced that somebody holding your hand or touching you in a supportive way helps in coping with aversive situations, and so this study is a timely, systematic demonstration of this with a nice investigation of underlying mechanisms,” she added.

The research appeared in the September 2019 issue of PAIN.

Handholding relief

Touch is an inherently social sense, important for promoting healthy physical and psychological development as well as bonding between individuals. Recent studies have demonstrated that touch can reduce pain associated with medical procedures in babies and experimental pain in adult partners (Gursul et al., 2018Goldstein et al., 2016). But how handholding in particular affected pain remained unclear.

“I have always been fascinated by the psychological and brain mechanisms that mediate different forms of analgesia,” López-Solà explained. “At the time we were conceptualizing these experiments, very little was known about the effect of handholding on the perception of pain. We knew that there were reports to suggest that it worked, but there were no reports of the brain mediators of handholding analgesia. So we set about to investigate how handholding affected pain intensity, pain unpleasantness, and the impact on the relationship between the couple,” she added.

The study consisted of two phases: a baseline phase and a handholding phase. Both phases were run in an identical manner except that during the baseline phase, the female partner held an inert rubber squeeze ball, while during the handholding phase, she held the hand of her male romantic partner. A noxious heat stimulus (47°C for 11 seconds) was applied to the opposite forearm while the female was lying in an fMRI scanner. Following the painful stimulus, females rated pain intensity using the visual analogue scale as well as the unpleasantness of the stimulus. The researchers also recorded measures of emotional comfort such as perceived relationship quality and closeness to one another.

Handholding greatly reduced the reported pain intensity and pain unpleasantness in females, compared to holding the rubber squeeze ball. In addition, subjects reported greater emotional comfort along with a higher perceived relationship quality between the partners. Together, the results showed positive consequences of sharing the burden of a painful experience with another person.

Sensory and emotional systems engaged

After analyzing the fMRI data, the researchers found that handholding between the partners reduced a pattern of brain activity that this group and others previously found to be sensitive and specific to physical pain, known as the Neurologic Pain Signature (NPS; see PRF related news here and here). The NPS contains regions such as the somatosensory cortex, the anterior insula, and the anterior cingulate cortex (ACC). In this case, NPS ratings were significantly reduced during the handholding phase, compared to the baseline phase.

“The fMRI analysis more directly tied the subjective experience of analgesia with how the brain was modified during the process of painful stimulation in the presence of the handholding partner,” said López-Solà.

The effect of handholding in reducing the NPS is interesting, as recent evidence showed that the NPS is largely unaffected (showing no reduction) by placebo treatment, and, arguably, handholding could be considered a placebo. The impact of handholding on the NPS in the current study piqued Leknes’ interest.

“It’s interesting that they made the point that the mechanisms of handholding are distinct from placebo in terms of the NPS, as you could envisage placebo as a cue of social support, such as simply receiving attention or care from a medical professional, similar to handholding.”

Although NPS responses were reduced during handholding, this did not correlate with the subjective reports of decreased pain intensity and unpleasantness in the study participants. This suggested to the researchers that NPS reductions were unlikely to fully explain the analgesic effects of handholding, and that other brain regions may be involved. Indeed, further in-depth analysis of the fMRI data revealed that handholding increased the functional connectivity between the NPS and what is known as the default mode network.

The default mode network includes the medial prefrontal and posterior cingulate cortices, and generally is active when a person is not engaged in any demanding cognitive task but is in a resting state. It’s closely associated with one’s “inner state” and self-referential thoughts such as the appraisal of incoming information to determine how it will affect an individual (whether it’s good, bad, or dangerous, for instance), as well as with trying to gauge the thoughts of others. Furthermore, handholding-related reductions in pain were also associated with brain activity reductions in areas such as the amygdala and ventromedial prefrontal cortex, regions involved in processing defensive reactions and stress.

“The NPS is telling us that there is something at the basic nociceptive level that seems to be reduced by handholding. But there appear to be other regions, outside of the NPS, involved in directly mediating the reductions in pain intensity and unpleasantness, and these regions are in a circuit that is more closely related to emotional and stress responses as well as the evaluation and generation of the meaning of stimuli,” according to López-Solà.

Peripheral influences

One of the questions raised by the work is whether handholding is merely a distraction from pain. Holding the rubber squeeze ball didn’t produce reductions in pain intensity or unpleasantness, nor did it reduce the NPS, compared to handholding. That suggests that distraction via peripheral stimulation is not sufficient to produce the sensory and emotional effects seen in the study.

López-Solà believes there is a strong central component to the phenomenon of handholding analgesia.

“It’s hard to say conclusively whether or not the results are driven in part by peripheral input. However, the strong involvement of multiple limbic and neocortical regions that we see should be less directly influenced by pain primary afferents,” López-Solà said. “They require contextual information, such as meaning and representation of your romantic partner, which the brain is better able to encode compared to the periphery.”

Leknes suggests an additional experiment to learn more about the effects of the supportive touch of a romantic partner on pain.

“You can’t distinguish the effects of holding your partner’s hand versus holding a stranger’s hand based on the current results,” according to Leknes. “Another way to address the specifics of having your partner touching you would be to have them in the room not touching you, all of which could tell us more about the nature of touch and its influence.”

Dara Bree is a postdoctoral fellow at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center and Harvard Medical School, Boston, US.